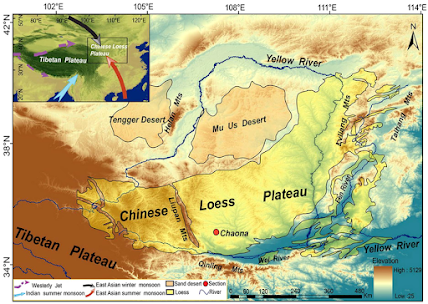

This book by Ruth Mostern was a great study of hydrological history. Mostern's writing is a little dry, but it's a work of scholarship that really taught me a lot about a river I knew nothing about. The Yellow River is China's second-longest river, after the Yangtze (meaning Long River), and is the sixth longest river in the world. It is also the birthplace of Chinese civilization. It feeds a floodplain in northeastern China that is extremely rich agriculturally, but it also causes massive floods that kill and displace millions in the worst events. Here is a map below.

By Shannon1 - Created using Natural Earth and NASA SRTM data, both public domain., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9617583

The most interesting thing I've learned is that the Yellow River was not always yellow. It is called the Yellow River because of the color of the river after it picks up sediment in the Loess Plateau (see below).

But originally, sediment didn't run with the river. In fact, the sediment comes from erosion caused by human activities: felling trees, grazing animals, and clearing land for agriculture. All of these activities removed plant life, causing more erosion, which washed sediment into the river until it reached the flat floodplain (see below).

As the water reached the floodplain, it deposited the silt, which would then block its own path, causing the river to wind across the plain, continually changing course, forming oxbow lakes, and gradually rising above the land surrounding it as it travelled on its own silt beds. Being higher than the other land, when the river did spill its banks, the floods were more dramatic, as the river couldn't connect back to its old course, which was higher than the surrounding land due to the silt deposits.

Until the ninth century CE, relatively few people lived upstream on the Yellow River, and there were a far smaller number of flooding events downstream than would occur later. It was then that the Chinese state sponsored major frontier colonization up into the middle reaches of the river, doubling the rate of erosion (today, the rate of erosion is ten times natural levels). Before that, as recently as 2,500 years ago, historical documents, pollen records, and archaeological sources show large areas of shrubs and grassland, which today cover only 3% of the Plateau. The Loess Plateau receives less than twenty inches of annual rainfall, and 90% of the river's sediment comes from there, as almost all of the Yellow River's middle-course tributaries funnel into the plateau region. The erosion has grown exponentially: between eleven thousand and six thousand years ago, the river deposited about .54 centimeters of sediment annually; between six thousand and three thousand years ago, .75 centimeters; and today it deposits 8.2 centimeters per year, fifty-eight times the rate of the early period. The smaller numbers were already enough for the river to overflow its banks, but during the beginning of greater human intervention 1,000 years ago, the river started to rise by about a meter a century.

The first major state-sponsored colonization of the frontier began under the bureaucrat Shang Yang during the Qin dynast in the fourth century BCE. First, Qin laborers built a wall, staffed with soldier-farmers to keep out the horse-riding raiders and to demarcate the area of agricultural activity; then, they surveyed and subdivided the kingdom, assigning new land uses, intending to farm in areas where they probably shouldn't have, very similar to the US in the Great Plains in the 19th century. Agriculture intensified south of the wall, and the Qin forbade the older system of migratory, interlocking subsistence farming. The Qin dynasty would end up unifying China as its first modern empire, and the Qin regime sponsored as many as eleven forced migrations to the northwest onto the Loess Plateau.

Within a few centuries, contemporary scholars and bureaucrats were already noticing that there was an erosion problem. Zhang Rong, commander in chief at the Han imperial court, observed in 4 CE that state sponsored colonization caused erosion and flooding. Unfortunately, changes were not made, and it was probably already too late. A catastrophic flood broke through the levies in 14 CE, and the river was not rerouted until 70CE. Mostern observes that between the census counts of 2 and 140 CE, the total population of the Han empire declined from 58 to 48 million, and there was a massive exodus out of the Yellow River floodplain: in 2 CE, 44 million people lived in north China and 14 million in the south; but in 140, 26 million lived in the north, with 22 million in the south. But even so, this was a more stable system than the shock that would come in the tenth century.

Flooding got really bad during the very wet 920s, in which heavy rains caused more sediment wash. Every year between 924 and 954 saw at least one flood or breach, and then beginning in 958, there were annual disasters, usually more than one. Only seven years between 958 and 1029 didn't have a massive flood, and in three years, there were double digit numbers of floods. Here is a graph below made by Mostern of the flooding. You can see that things get really bad in the tenth century and then periodically hit bad levels for centuries after.

This period in the tenth century, coinciding with the transition from Tang to Song rule, is considered by historians to be a major watershed in imperial Chinese history, in which there was access to new strains of faster-ripening rice, population doubled (and urbanized), and Chinese civilization became more oriented toward the Yangtze River than the Yellow River. Until the eighth century, less than half of China's population lived south of the Yellow River basin, but by 1550, over two-thirds did. The shift probably came around the tenth century, according to Mostern. She doesn't say it directly, but it would seem to be the implication that poor river management caused catastrophe after catastrophe and drove people away.

It's crazy to read how many people knew exactly what was going on with flood management and were ignored. Liu Tianhe (1479-1545), a minister who served as a military officer in Shaanxi, wrote A Compendium of Questions About Water (Wenshuiji), and identified that

[Silt] comes down from the gullies that have come to exist in the high-altitude places in the northwest, from whence the water rushes with extreme violence that levees are unable to resist. Second, the silt raises the riverbed higher, so today, if one surveys the middle of the stream as it flows through Kaifeng, [one discovers that] in winter and spring, it has a depth of only a bit more than one zhang, while even in summer and fall it does not exceed more than two zhang. Its bed is high, unlike the abyss of the Changjiang [Yangtze] course ... Fourth, downstream, the land is extremely flat and there are no mountains to control and confine [the river]. Fifth, in all of the former northern and southern courses of the [river] through the central prefectures, the earth is mixed with mud and sand. Sixth, this perfectly causes [riverbank] collapse through susceptibility to breaches.

It seems like, according to Mostern, the CCP made the most progress at flood control. By the 1950s, they basically understood what was going on, and began to restore forests and grasslands on the Loess Plateau while also building new concrete embankments with steel foundations on the floodplain that were far stronger than anything built before. But problems aren't over. The Yellow River has experienced desiccation (drying up) multiple times since the 1970s, and the rate of desiccation has increased with time. What water remains is polluted with fertilizers, pesticides, and industrial chemicals. This is surely a big issue for the future.

Miscellaneous Facts:

- The Great Bend in the Yellow River, which turns north, then east, and then south before turning east again, is a result of a shift in continental plates long after the Yellow River first formed 56-34 million years ago. It had drained due east until India crashed into Asia five million years ago and caused the "Ordos Block" to fold and uplift into place.

- The Yellow River did not originally take one clear path to the sea, but just sort of petered out on the floodplain. It had to be channelized to actually clearly make it to the sea.

- The major turning points in soil erosion occurred about 7,000 years ago, with the emergence of neolithic agriculture; 300 BCE to 0 CE, as a result of state-directed Iron Age agriculture; between 800 and 1100 CE, the most abrupt change due to population growth, military activity, and timber commodification; and in the 17th and 18th centuries, when people began intensive dryland farming of maize and tubers with a population boom.

- Around the eighth century BCE, pastoralists started riding horses, which introduced the horse population to the landscape, eating up lots of grass and causing more erosion.

- Kublai Khan commissioned the first scientific expedition to the headwaters of the Yellow River in 1279, which resulted in a short book titled Monograph of the River's Origin (Heyuan zhi).

No comments:

Post a Comment