Introduction

Let me just

say that while this was an incredible book, I do not recommend it to anyone who

unless you are extremely invested in deeply learning about the Thirty Years

War. This was a very interesting book, but extremely detailed and I wish I had

chosen something half as long. I felt like I was not able to learn as much as I

could have because I was just overloaded with so any details it was impossible

to keep track of all the characters, the armies, and the places. What follows

is my best understanding of the war from the book and a little bit of

Wikipedia.

The Legacy of the War

The Thirty

Years War was an unprecedented catastrophe in Germany that would not be matched

until the 20th century. I had no idea of this. Wilson writes that Albert Speer,

Nazi architect and armaments minister, announced on May 4, 1945, as Germany was

laid waste by Allied forces, that “the destruction that has been inflicted on

Germany can only be compared to that of the Thirty Years War. The decimation of

our people through hunger and deprivation must not be allows to reach the

proportion of that epoch.” And for that reason, the Nazis surrendered. Wilson

writes that surveys in the 1960s found that Germans listed the Thirty Years War

as Germany’s greatest disaster, ahead of the world wars, the Holocaust, and the

Bubonic Plague. He writes that Germany was more devastated during the Thirty

Years War than any other time in its history, even the calamities of the 20th

century.

The Holy Roman Empire and its Organization

The Holy

Roman Empire at the dawn of the Thirty Years War was ruled by Habsburg emperors

and 50-60,000 noble families. Most of them were “territorial nobles” who just

owned some land under the jurisdiction of lords with imperial fiefs of whom

there were 180 lay fiefs and 130 spiritual fiefs. The Habsburgs themselves

controlled over 40% of the land in the Empire, governing 7 million of the HRE’s

24 million subjects. This gave them a virtual monopoly over the title of

emperor from 1438 until the fall of the empire in 1806, as very few other lords

had more than 100,000 subjects.

Questions Unanswered by the Peace of Augsburg

The Peace of Augsburg in 1555 gave

lords the right to choose the religion of their lands and laid the legal

groundwork for toleration of both Lutheranism and Catholicism. While it was

written to be ambiguous, not even using the term “Lutherans,” and speaking in

euphemisms, there was no major war for another 63 years after the treaty, with

only localized conflicts. However, there was diverging interpretation over

three items, known as The Three Dubia.

First, could there be

Protestant bishops ruling fiefs in the HRE? The emperor dodged the issue by

calling them administrators instead of bishops, and their rulers were given

essentially secular authorities. In the late 16th century, more ecclesiastical

territories fell to Protestants, putting pressure on the Catholic majority in

the Reichstag, the HRE parliament. The second issue was what to do with

ecclesiastical property that was within the jurisdiction of a Lutheran ruler

that had not already been incorporated into his territorial church property. It

was a point of controversy how much power Lutheran rulers could exercise over

those institutions. The third and final issue was what the religious freedoms

of the subjects were. This was especially contentious in territories where the

lord was Catholic ruling over Lutherans and vice versa. This question also grew

more pressing in the late 16th century when Catholic rulers tried to enforce

religious conformity to prove loyalty.

The State of Religion Before the Thirty Years War

After the 1555 agreement,

Catholicism came under intense pressure in the late 16th century. Nine in ten

Lower Austrian nobles embraced Lutheranism as well as 85% of those in Upper

Austria, where three in four urban-dwellers and half of the peasants were

Protestants as well. 70% of Inner Austria was also Protestant and only five out

of 135 Styrian nobles remained Catholic. The Habsburgs, who remained Catholic,

were forced to recognize the rights of their lords to be Lutherans and gave

them assurances of religious freedom. Nobles were allowed to worship in their

own town houses, which became de facto churches. In many regions, nobles paid

off Habsburg debts in exchange for assurances of religious freedom, such as the

Pacification of Bruck, which seems to come up a lot in the early part of the book.

Catholics were a minority in Croatia and Tyrol, but no Protestant religion

gained complete acceptance.

As the Reformation went on,

everyday life became more divided by the end of the 16th century. You could

tell by people’s names: Joseph and Maria were especially popular among

Catholics while Calvinists rejected saints’ names and used names from the old

testament like Abraham, Sarah, Rachel, and Daniel. Protestant territories spoke

Luther’s Saxon dialect of German, while the Jesuits taught High German in the

south. Calvinists rejected theater, while Lutherans and Catholics continued to

use it in schools. Catholic sermons focused on Madonna and the saints while

Lutherans and Calvinists focused on morality. Even calendars were different

since Pope Gregory XIII set the date back by ten days on October 15, 1582,

making the new year start on January 1 instead of March 25. Of course

Protestants were very reticent to follow the new, “Catholic” calendar.

“The Way of War”

There is a

great chapter in this book called “The Way of War,” covering military

technology, tactics, and theory at the start of the 17th century. The most

interesting assertion Wilson makes is that the pace of technological change had

slowed from the mid-sixteenth century onward, as “all the basic weapons had

appeared while further developments were restricted by manufacturing problems.”

He uses cannons as an example of weak production. Most interestingly, he

expounds on how all the major weapons of war for the next several centuries had

already been invented in one primitive form or another. Poison gas shells were

used in the Netherlands, and firebombs were already invented by heating shot to

ignite tightly packed buildings. Shells were using flint and steel detonators

and cannons were already being stuffed with antipersonnel round that spread out

on being shot, a sort of massive shotgun. Wilson asserts that further

developments were just refinements on the basics that were all there, as the

modern age of warfare had begun. I won’t go into all the details of this, but

they are fascinating.

Prelude to War

A Weakened House of Austria

Between the

1590s (the start date is controversial) and 1606, the Ottoman Turks and the

Hapsburg HRE fought an indecisive conflict that drained both sides’ resources. It

was fought mostly in Hungary, then a borderland between the two empires.

Although it was a boondoggle for all involved, it had the benefit of weakening

the Ottomans such that they would not compete in the Thirty Years War, although

the Turks would remain a source of anxiety for Habsburg rulers. On the other

hand, the war weakened the Habsburgs so much financially that it may have

contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years War by weakening the ruling

dynasty. The Long Turkish War was the largest mobilization of troops in the HRE

in decades, and the soldiers who gained experience as officers became the

preeminent generals of the first half of the Thirty Years War. The war did at

least manage to end the annual tribute the Habsburgs had been paying to the sultan,

so that was nice.

Wilson

writes that “the ensuing ‘Brothers’ Quarrel’ compounded the damage” of the Long

Turkish War. Rudolf, the emperor, and his brothers, Matthias, Maximilian, and

Albert basically engaged in politicking against each other after the war that

resulted in Rudolf abandoning plans to fight the Turks again and relinquishing

power in Hungary to Matthias while granting greater autonomy Bohemia (modern

Czechia). After the war and the subsequent loss of central power, the Austrian

monarch Rudolph II was significantly weakened

The Powerful Spanish Habsburgs

Meanwhile,

the Spanish Habsburgs were at their strongest. They were discovering silver in

their possessions in the western hemisphere and conquering territory. However, after

the death of Philipp II, the empire was on autopilot under his weaker, less

able son, Philipp III. For reference, Philipp II is the uncle of the brothers

discussed above and Philipp III is their cousin. Philipp III is also the

brother-in-law of Albert, who married II’s daughter and III’s sister. Philipp

III also married their cousin from another branch, Margarethe. I know, what the

fuck were these guys doing. Anyway, Wilson is a little defensive of Philipp

III. He notes that historians have been really critical of him, calling him the

laziest ruler Spain has ever had. His own father is quoted as saying, “God, who

has given me so many kingdoms, has denied me a son capable of ruling them.” I

wonder if Philipp III ever heard him say that. However, Wilson writes that Philipp

III attended meetings of council daily from age 15 and retained the final

decision on all important matters. It sounds like he was a bad ruler who looked

even worse because his father was maybe the greatest ruler in Spanish history.

Spanish

crown, had been in revolt. That is ten years before Philipp III was even born.

It would end up going on for 80 years, until the end of the Thirty Years War.

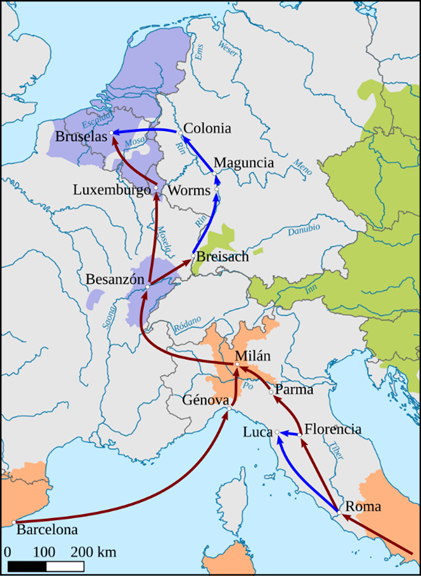

It drew Spain into continental politics, since the Spanish used a route called

the Spanish Road to reach the Netherlands.

The “road” actually started with a journey by sea from Spain’s

Mediterranean coast to Genoa, where men marched to Milan, and joined with

troops from Spain’s Italian possessions. Then, they crossed through the

territories of the Duke of Savoy across the Alps and then along the Rhone River

through Franche-Comte. Then they moved north through the Duchy of Lorraine into

Luxembourg before arriving in the Low Countries. Sea travel would have been

much faster, but the overland route was safer. Wilson writes that Spain sent

over 123,000 men this way between 1567 and 1620, as opposed to 17,600 by sea. The

map shows Spanish possessions in orange, Austrian possessions in green, and

Spanish dependencies in purple.

The Northern Powers

While Spain

and Austria (Austria also controlling most of Germany) were stagnating, Denmark

and Sweden were emerging from civil wars and growing stronger, while the Polish

Lithuanian Commonwealth was entering its golden age.

Denmark,

although newly stable, was still poor. Wilson calls the monarchy of Denmark at

the time a “domain state,” meaning that it was heavily reliant on income from

crown lands, which made up 67% of revenue in 1608. The economy was based on

barter, and taxes were usually paid in food. Some of the food fed the royal

court, and the rest was sold at market for cash. However, Denmark was entering an economic

boom at the start of the 17th century. Revenue rose year after year and

Christian IV of Denmark, who would rule until 1648 became the third-richest man

in Europe, after Duke Maximilian of Bavaria and his own mother, who died in

1632. This made him the unusual creditor-king, allowing him to maintain the

loyalty of his courtiers and subjects through debt. This is the opposite of the

usual situation in Europe at the time in which monarchs constantly had to

borrow from the nobles. However, the wealth of Christian IV was not very stable

because it allowed him to engage in foreign adventures that would impoverish

the crown, and could not last long enough to sustain a long war, say one that

would last for thirty years…

Upon the

death of his father, Charles IX, in 1611, the seventeen-year-old prince

Gustavus Adolphus became King of Sweden. The build-up for this guy in the book

is amazing. He is supposedly the ideal king, able to converse with peasant and

noble alike without losing his royal bearing yet still seeming relatable. He

had a loyal chancellor who was his partner and the two were a sort of John and

Paul of their time, making Sweden briefly an extremely important player in

European affairs. In their first six years, they focused on getting the country

out of Charles IX’s conflicts. Then, they turned to domestic reforms. In 1621,

when Gustavus Adolphus was just 27, he went to war with Poland (until 1629),

finally intervening in Germany in 1630 before dying two years later as a hero

of the Protestant side of the Thirty Years War. He would be succeeded by his

daughter Christina, later considered one of the most leaned women of her time.

But that is all in the future. What is important at the dawn of the Thirty

Years War is that Sweden was making military reforms that would last until the

20th century because they were so successful, and his intervention in 1630 will

significantly impact the war.

Factionalism in Germany

Two paths

emerged for the Protestants of the Holy Roman Empire. Saxony (northern Germany)

led the moderate path, trying to work within the Reichstag to chart a course

for Protestants in the Empire. The Palatinate (southwestern Germany on the

Rhine) led a more radical path, pushing for the development of a formal group

outside the Empire’s power. In the 1580s, most princes of the Empire preferred

the Saxon way. The Saxon-aligned princes included Hessen-Kassel, Wurttemberg,

Pomerania, Mecklenburg, and the Ernestine line of the house of Wettin, which

controlled much of Thuringia in central Germany. Saxony later extended its

alliances in 1614 to include Brandenburg in the northeast.

With great

power in the Saxon elector’s hands, things changed when Christian I took power

in Saxony after the death of his father. He opened negotiations with the

Palatinate in 1590, resulting in the Union of Torgau in 1591, an agreement

intended to unite the two political branches of German Protestantism, and, in

Christian I’s mind, make the Palatinate more moderate. But the alliance was

fragile, and when Christian I died young and unexpectedly, rumors swirled that

he was poisoned by the Saxon Lutheran establishment for getting too close to

the Calvinist Palatinate. Christian II ascended to the throne at eight years

old, and Saxony became politically passive, as his mother aligned the duchy

with the Catholic Habsburgs. One privy councilor wrote in 1610, “politically

we’re papists.” With Saxony weak, the Palatinate took a starring role in the

partnership.

Fourteen

months later, the Catholics realized they needed to do the same, now known as

the Catholic League. Many of the most powerful Catholic electors and dukes did

not want to create a sectarian alliance. Mainz preferred to negotiate with Saxony

(a dead end). The electors of Trier and Cologne wanted to include Emperor

Rudolf, who had no interest in joining, so that was not going to work.

Maximilian of Bavaria didn’t want to join any group for the opposite

reason—fear that the Habsburgs would join and he would be overshadowed. But by

July 1609, Maximilian had changed his mind, and formed an alliance with the

bishops of Augsburg, Konstanz, Kempten, Passau, Regensburg, Ellwangen, and

Wurzburg. They envisioned a nine-year defense pact dedicated to defending

Catholicism. I unfortunately can’t find a map of the Catholic League

territories, but I did find a map of the state of religion in 1618 at the dawn

of the war. It shows Lutherans, Calvinists, Zwinglians, Hussites (Czechia), and

the Catholics. Protestants are in orange/red, Catholics are in purple. Lands

controlled by the Muslim Ottomans are in the bottom right also in red for some

reason.

The Return of the Brother’s Quarrel

Power

transitioned from Emperor Rudolf II to Emperor Matthias in two stages: first,

Matthias stripped his brother of his remaining power, and then Matthias

convinced the electors to accept him as successor. How this happened was

honestly very confusing in the book and I had to go to Wikipedia:

In November 1600 at Schottwien the

Archdukes Matthias, Maximilian and Ferdinand signed an agreement of concerted

opposition against the emperor, in 1606 declared Rudolf insane (document dated

25 April), appointed Matthias as the head of the family, and began to oust

Rudolf. It was Matthias and not the emperor who had brokered the Peace of

Zsitvatorok with the Ottomans and in 1606 had ended the conflict in Hungary by

granting freedom of religion in Hungary and guaranteed the right of

Transylvanians to elect their own independent princes in the future.

As unrest resurfaced in Hungary and

spread into parts of Moravia and Austria, Matthias attempted to utilize this

opposition in the power struggle against the emperor. He joined the rebellious

Diet of Hungary and the Lower and Upper Austrian estates in Bratislava in 1608

and in Moravia shortly later. In April 1608 Matthias marched on Prague and

besieged the city. Although unable to fully win over the Bohemian estates, he

forced Rudolf to negotiate and sign a peace treaty in June 1608. This, unsurprisingly,

resulted in the redistribution of power. Rudolf kept Bohemia, Silesia and

Lusatia and Matthias received Hungary, Austria and Moravia.

Rudolf surrendered the crown in 1611 and was confined to his

apartments. At this point, Matthias had Austria, Hungary and Bohemia while his

brothers Maximilian and Leopolld controlled some territories. Max had Tirol and

Leo was bishop of Strasbourg and Passau. Their cousin, Ferdinand, ruled Inner

Austria.

Matthias was finally able to gain

the throne in 1612 and found initial successes. The Catholic League dissolved

and the Protestant Union was “marginalized and on the verge of collapse” in

1618. The Reichstag met again and was able to recess normally in 1613, and

confidence was restored in the Habsburgs. However, the royal family was still

relatively weak and vulnerable to attack. While Matthias had once been the more

energetic and dynamic brother, it seems that once he gained the throne, he had

little energy left to rule. He did not have a head for detail, and critically,

he had no heir (the electors actually gave him and his wife a crib as a wedding

present). So perhaps it was a good thing that he preferred to spend time with

his young wife (half his age), but it meant that he went into the background of

imperial politics while his advisor Bishop Klesl entered the foreground. No

heir would come.

When the Reichstag met in 1613, the

Palatine representative led another walkout when the Protestant demands were

not immediately met in full. The remaining delegates managed to grant the

Emperor (Matthias) some money for frontier defense and recess to save face.

Bishop Klesl decided to delay another meeting of the Reichstag due to the rival

alliances. It would not convene again for another 26 years.

Because Matthias could not produce

an heir, his succession became a major question, as he was already 55 when he

gained the crown. Spain (for a myriad of reasons discussed in the book) decided

to back Matthias’ cousin, Ferdinand.

However, it should be noted that there was a sort of phantom candidacy

for Maximilian of Bavaria, then the richest man in the world. Christian of

Anhalt, the staunch Calvinist even approached the Catholic duke to propose they

merge their Protestant and Catholic alliances to kick out the Habsburgs. It didn’t

work out. Instead what happened is the Habsburgs cut a deal amongst themselves

in which Philipp III of Spain renounced his claims to Bohemia and Hungary, but

giving his sons claims over Ferdinand’s daughters, in exchange for a future

gift of an Austrian province. However, a secret deal was struck. Ferdinand

promised to marry Philipp III’s daughter and to surrender Austrian parts of

Alsace to Spain and Ferdinand would be made heir to Matthias and therefore the

Holy Roman Empire.

War Erupts in Bohemia

1618

Wilson

writes, “it proved impossible to contain the violence which kept drawing in

outsiders. The rapid internationalization of the conflict is deceptive. Europe

was not poised for war in 1618, as all the major powers remained afflicted by

their own problems. Therein lay the danger. With their rivals apparently

preoccupied, each power felt safe to intervene in the Empire. Few intended

their involvement to lead to a major war, and no one thought of a conflict

lasting thirty years.”

I would say

that one of the biggest things I’ve come to understand from this book is that

the Thirty Years War was really a series of different wars that in retrospect

make up one pan-European conflict. The Bohemian revolt that sparked it was over

in just two years. But things played out like one of my Crusader Kings games,

where just as you finish defeating one revolt and are weakened, a rival power

declares war on you or another revolt breaks out, taking advantage of your

vulnerability.

The

Bohemian revolt was an “aristocratic coup” brought about by a small group of

militant Protestants. These militants decided to throw three representatives of

the crown out a high window, which was actually the third defenestration of

Prague. I don’t know how this keeps happening. But basically, it was a super

high fall. Luckily for these guys they all lived, and one of them who kind of

slid along a slanted side of the building was able to get them up and to

shelter and safety. Protestants claimed that they fell into manure, and

Catholics claimed that the Virgin Mary laid out her holy cloak to bring them

safely to ground. Who can say what really happened? Most importantly, one of

the men who was thrown out the window was made a lord with the dynasty name

“Von Hohenfall” (of the high fall) and that is hilarious.

The

Bohemians quickly announced that they no longer recognized the Holy Roman

Emperor Ferdinand II as their king, but rather they elected Frederick V,

Elector of the Palatinate, and leader of the radical Protestant faction. One

really strange thing about all of this is how slow things move. The

defenestration happens in May 1618, and from that point, Bohemia is in

rebellion. It’s not until August 1619 that the Bohemians name Frederick as

their king, and not until 1620 that a decisive battle is fought. It is crazy

how slow the empire was moving to stop this. That same month, Gabriel Bethlen,

the Calvinist Prince of Transylvania, invades Hungary. So it’s a shitshow. At

this point, the Habsburg monarchy is in serious peril. Ferdinand II was in

massive debt, and only surviving on subsidies from Spain and the Papacy, so

that’s why the response was so slow. This was how Maximilian of Bavaria was

able to gain an advantage. Max slowly prepared to revive the Catholic League,

ostensibly not led by him, and reactivated it in October 1619 at Ferdinand’s

request, providing the legal basis for his future actions. Max used his

leverage to get Ferdinand to declare Frederick an outlaw, entitling Emperor

Ferdinand to seize his lands, which Max of Bavaria had his eyes on. In an

agreement with Maximilian, Ferdinand agreed to give the Palatinate’s elector

vote to Bavaria (used to elect emperors). In November 1620, Ferdinand’s troops (led

by Tilly and Wallenstein) win a decisive victory against Frederick’s (led by

Christian of Anhalt) in the Battle of White Mountain and go on to sack Prague. Frederick

V was starting to be called “The Winter King,” as he only ruled for a single

winter. He went on the run. In the meantime, Ferdinand negotiates a peace with

Bethlen who sees he’s outmatched.

It seemed

like peace was possible in 1621 and that the crisis was over. The Catholic League

even voted to reduce its army’s numbers to 15,000. However, Frederick was

intransigent. The Saxons mediated talks in which he declared that he would

renounce Bohemia and accept Ferdinand as king, but only if Ferdinand confirmed

full religious liberty, assume all of Frederick’s Bohemian debts, and refund

Palatine military expenses from the rebellion. This was obviously insane, and

Ferdinand put the major leaders of the revolt under imperial ban, paving the

war to confiscate their lands and titles. Frederick became more inflexible and

decided his only hope was to fight on.

The Palatinate Campaign

At this

point I got lost and had no clue what was happening. So I consulted Wikipedia a

bit for this part. In 1620, while Catholics and Protestants were fighting at

White Mountain outside Prague, the Spanish decided to occupy the Palatinate

while Frederick was gone due to its proximity to the Spanish Road. It happens

that Frederick was married to the daughter of James I of England, who

threatened the Spanish, but they were able to open up negotiations. Sensing

Spanish weakness, the Dutch restarted the Eighty Years War in 1621, and offered

military support to Frederick to regain his lands, which could be used to

threaten the Spanish Road. The Catholics won this stage of the war too.

Ferdinand granted Frederick’s titles, lands, electoral vote, and lands to

Maximilian of Bavaria, despite opposition from Protestants in the Empire and

the Spanish. During this portion of the war, Britain allowed the powers to

recruit from them, and ended up sending huge amounts of troops to fight in the

war.

At this

point, the Catholics were ascendant. Ferdinand consolidated his hold on

Hungary, and confirmed his son, also named Ferdinand, as King of Hungary in

1625. Catholic influence grew again in Hungary. In Bohemia, the Battle of White

Mountain was long thought of as a critical turning point in Czech history,

ushering in a dark age for the Czechs. When the Czechs broke from the

Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, a large crowd gathered on White Mountain

battlefield to hear speeches declaring triumph over the shame of 1620. But

Ferdinand was not in possession of complete victory in 1625. Frederick V still

lived, and his rights were the basis of Danish intervention in Saxony that

year. The Empire was still fundamentally financially unsound. Ferdinand was now

even deeper in debt and soldiers would not disband their regiments until

paid. He used incomes from his

hereditary lands and confiscations of revel lands to raise money and even

created waiting lists to gain lands, which individuals could trade positions on

for cash; but it was fundamentally the personal relationship of Emperor to

subjects that sustained the HRE in this time.

One

fundamental issue for the imperials and Catholics was the disunity of their

forces. The Catholics, led by Maximilian of Bavaria, were allied to the

imperials, led by Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor. However, their armies were

not united, with the Catholic League’s forces led by Tilly and the imperial

army led by Wallenstein. The two jockeyed for power and disagreed frequently,

and Wallenstein tried to resign six times between February and March 1626 due

to Tilly’s refusal to join his troops with Wallenstein’s.

Another

problem for the imperials was that re-Catholicization was not going well. In

many regions where the church was restored to power, peasants were now

revolting. The Bavarians were able to crush revolt in Austria, but Ferdinand

was forced to delay re-Catholicization measures until 1631.

Denmark Invades: 1626-1629

The period

of the war from 1626-29 is marked by an invasion of Denmark by King Christian.

Christian asserted Frederick’s rights to Bohemia, but lost in his invasion. It

appeared that peace was at hand, but the intransigence of Ferdinand and

Frederick got in the way once again. Frederick finally offered a compromise,

saying he would renounce Bohemia, accept Maximilian as an elector as long as

the title reverted to the Palatinate on Maximilian’s death, and submit to

imperial authority by proxy to avoid personal humiliation. But Ferdinand

demanded that Frederick submit in person, and a deal was not reached.

After

triumph against Denmark, the powers that be in the Empire thought that the war

was over. As a result, the electors voted to reduce the size of the imperial

army, as Wallenstein was unpopular already and of course they didn’t like to

submit to imperial power. Tilly’s Catholic League army remained strong.

Ferdinand became less popular when he granted Mecklenberg to Wallenstein in

1628, the same year that he officially make Maximilian a hereditary elector and

gave him much of the Palatinate, upsetting the balance of power in the HRE.

Ferdinand further upset the balance of power in 1629 by issuing the Edict of

Restitution, setting out his intention to return lands taken by Protestants to

the church, which angered the Protestants who had remained loyal and made peace

harder to reach, as the rebels had more to lose now if they surrendered. Even

the Catholic Habsburgs in Spain opposed the Edict, correctly fearing that it

would prolong the war. Re-Catholicization was seemingly a doomed effort. Even

when the Catholics succeeded in taking back their churches, they lacked enough

monks, nuns, and priests to fill them. The quality of Catholic clergy declined

in this era.

Ferdinand

was now isolated from his nobility, and when he tried to remove doubts of

succession by proposing his son as his heir, the electors refused until other

issues were resolved. Instead, they demanded Wallenstein be dismissed, but

failed to accomplish this.

Swedish Intervention: 1630-1632

Gustavus

Adolphus was first and foremost a conqueror. Nominally a Protestant, his

chancellor, Oxenstierna later admitted that religion was a pretext for war, and

Gustavus himself said that if religion were the cause he would have declared

war on the pope. Gustavus Adolphus invaded to secure the security of Sweden,

strengthening it on the international stage, and to balance the internal politics

of Europe by weakening the Habsburgs. Additionally, the Swedish king didn’t

mind picking up all the plunder he could along the way. France made a deal to

fund Sweden for five years as it ransacked the HRE so long as it did not touch

Bavaria, with whom Richelieu had made a deal to defend Maximilian’s title.

Britain also backed the Swedes, as they hoped Gustavus would restore Frederick

(related to the King of England through marriage) to his seat as an elector.

The Swedes

used a huge among of German manpower, in fact making up the lion’s share of

their army. 46% of the Swedes who landed in July 1630 were dead within six

months, largely due to diseases that were unfamiliar to them in Scandinavia.

Adolphus lost 50,000 men by the end of 1631, at which point his army contained

only 13,000 Swedes and Finns, being mostly German. The annual attrition rate

was one in five, with most conscripts from Scandinavia living no more than four

years after arriving in Germany.

Despite those obstacles, the Swedes

were completely dominant on the battlefields of Germany. Gustavus Adolphus was

declaring significant chunks of the HRE liberated as he conquered them in his

own name and proved unstoppable for a time. With Wallenstein gone, Tilly could

not win against the Swedes and was killed in battle in 1632. Wallenstein was

restored as master of all the imperial and Catholic armies, and took

inspiration from the Swedes as he instilled greater discipline in his men.

Finally, Wallenstein confronted Gustavus at the Battle of Lutzen, where the

Swedes won the field, but Gustavus Adolphus lay dead with two bullet wounds. No

one realized this until after the battle was over, but it would turn the tide

of the war. Frederick V would also die in 1632.

The Latter Portion of the War, and the Point at Which I

Became Completely Lost

So at this

point in the book, I have to admit that I took a big defeat. I just could not

keep up with all the new names and battles and numbers of men fighting at each

battle and it was just killing me. I think the author has been good at

including the details but man I did not need this many details. The Holy Roman

Empire is just so hard to read about and this is a clusterfuck. I will try to

write down what I know and what is important.

When

Gustavus Adolphus died, his sex-year-old daughter, Christina, became queen. His

widow was distraught at the news of his death and locked herself and her

daughter in her room and blackened he windows. When her husband’s embalmed body

arrived, she visited it every day, and when they buried him, she dug him up. Eventually,

the courtiers seized Christina from her to be queen and banished her mother to

Gripsholm island in 1636. The Swedes started looking for a way to end the war.

However,

the Empire was not about to let the Swedes gain peace while they still held

power in Southern and Central Germany. They sent Wallenstein after Swedish

forces. Wallenstein was successful, and I could not tell you how because I was

totally lost at this point. But what I did figure out is that he was too

successful, and spawned jealousies and a plot to murder him. Soldiers had

grievances and blamed him, and the nobility never liked how he was able to

centralize military power. So they killed him. And by the way, in 1636, Emperor

Ferdinand II died and was succeeded by his son, Ferdinand III. I will just say

that at this point, about 20 years into the war, almost none of the major

players from the beginning are left. This was really a generational struggle

and it must have been easier to negotiate for peace at this point as all the

war-starters were dying. The only major character I see left by the time

negotiations begin is Maximilian of Bavaria.

I will also

say that by the 1640’s, this is really not just one war, but several. There are

the rebellions in the Empire, the Dutch Revolt against Spain, French invasions

of Germany, Spain, and Italy, the Swedish invasion of the Empire, Polish

incursions to protect their own interests, and so many more disputes. The war

has just become a black hole sucking every polity in Western Europe into its

lightless maw.

Peace Negotiations

Peace

negotiations began in 1643 and lasted five years until the Peace of Westphalia

in 1648. During that time, fighting continued, and the powers sought to win

victories in the field so that they could win victories in diplomatic meetings.

In fact, the Swedes arrived at the gates of Vienna to threaten the young

Emperor Ferdinand III in 1645. Certain disputes and powers were excluded. These

included tensions in the Baltic and the Balkans as well as the English Civil

War. Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and some minor Italian states were also

excluded.

But despite

those exclusions, the congress that occurred in Westphalia became one of the

most monumental events of all time. It blew my mind. There were 194 official

participants, with 178 coming from within the Holy Roman Empire. The other 16

participants were European states like Spain, Sweden, France, Denmark, and

Poland. Wilson writes that this was the first truly secular international gathering,

and that makes it hugely significant.

The powers

agreed that all kings had the title of “majesty” and that all royal and

electoral amabssadors could be addressed as “excellency,” and could arrive in a

six-horse coach. The model of this congress was used for hundreds of years

thereafter, at Utrecht (1711-13), Vienna (1814-15), and Paris (1919), until

eventually its form was standardized in the United Nations.

Critical to

the people who lived through the war was that the final settlement allowed

freedom of religion to princes, but forbid them from imposing their own theological

beliefs on their Catholic, Lutheran, or Calvinist subjects. Jews, Muslims, and

other heretics were excepted. Religious tolerance was not complete, or anywhere

near what it is today, but people were able to return to peace after the war.

Some places, like Augsburg, were split down the middle, and practiced

segregation based on religion, with guilds, taverns, and pigsties organized by

who was Catholic and who was Protestant. But in other places, like the village

of Goldenstadt, Catholics and Protestants agreed to share a church. Wilson

writes that this should not be considered progress but a return to the

pragmatism that existed before the war. Mixed marriages also resumed in many

places.

The Political Results

The

Habsburg dynasty was surely weakened after the war. The Spanish Habsburgs were

weakened by prolonged conflict, and Spain was now in decline from its early/mid-17th

century peak. At the end of the century, the death of an heirless monarch would

plunge Europe into the War of Spanish Succession. The Austrian Habsburgs were

now the predominant line, but they too were weakened, as the Holy Roman Empire

was now more decentralized than before the war. Eventually, the Habsburg rule

in Germany would weaken enough that they became a purely Austrian house as the

Prussians conquered the Holy Roman territories. That said, the Empire survived

another 150 years until Napoleon, the greatest military mind in almost two millennia,

dismantled it.

It seems

like the war is mainly a stalemate, but that if anything, resulted in more of a

Protestant victory and a Catholic defeat. Wilson writes that the public on all

sides was relieved that the war was over above all else, but that Catholic

celebrations were more muted than those of the Protestants. Catholics seemed to

sense that Protestantism was here to stay and that the role of the Catholic Church

would not return to its old predominance.

The Cost of the War

It is very

difficult for experts to say how many died in the Thirty Years War. In fact, it

is very difficult for experts to even know how many people were alive in Europe

at the time. However, the best estimates suggest that there was a 15 to 20

percent decline in population due to the war. This is immense. For scale, a 15

percent decline would make the Thirty Years War the most destructive conflict

in European history. For reference, the Soviets lost 12 percent of their

population in World War Two. So even by low estimates, the war was a horrific

disaster.

Conclusion

The Thirty

Years War is well-understood as a war of religion, but people should be careful

not to take that characterization too far. Religion was certainly the major if

not greatest aspect of the war. However, it was not the only aspect by a long

shot. Throughout the war, Catholics fought in Protestant armies and Protestants

fought in Catholic armies. Wallenstein even promoted several Protestants to

high positions in the Imperial army, which discriminated much less than others.

No one seemed to care what religion the ordinary soldiers were. And remember

that most soldiers in any army were not of the “nationality” that they fought

for. The French army contained a minority of Frenchmen, the Swedish army hardly

any Swedes and so on.

All in all,

this was a really informative book, and I feel like I just took a class in European

history. I do not plan on reading anything like this for a long time. Lol.

Miscellaneous Facts:

- The Jesuits were founded in 1540 with the mission to “extirpate Protestantism” in Wilson’s words. Jesuits were more political than other Catholic priestly orders, and they worked at the top of the political hierarchy, in the belief that winning over the elite of territory would lead to the rest of its society rejoining the church. Protestants have seen this as a papal conspiracy, which it sort of was, since the plan was to put Jesuit advisors in all the courts of Europe and have the elites send their children to Jesuit schools.

- Not really a “fact” but something I found very interesting was how the author compared Sweden in the 17th century to Prussia in the 18th century. Both were led by dynamic young kings who were military geniuses (Gustavus Adolphus and Frederick the Great), both states used paid professionals as a significant part of their armies, and both were poor states with agrarian economies that leveraged their manpower where they lacked gold.

- The low countries were the center of the European arms industry at the beginning of the 17th century.

- Rene Descarte was an observer at the Battle of White Mountain.

- When Duke Maximilian took control of the Palatinate, he appointed as governor Heinrich von Metternich, an ancestor of the Clement von Metternich who negotiated the “concert of Europe” after the defeat of Napoleon.

- Wallenstein commissioned Johannes Kepler to do his horoscope in 1608 and 1625. Wallenstein was obsessed with astrology.

- Rape was rarely prosecuted in the Renaissance/Reformation era. Official papers record rape only five times in Munich in the first half of the 17th century and three times in Frankfurt in between 1562 and 1695.

No comments:

Post a Comment